MuseWeb 2020 – Build or buy?

This blog post is full of links.

#mw20Capacity Planning for Meaning

“Because, there are no futures without histories.” (Jain, 2020)

Designing for patience

The idea of “designing for patience” is for cultural heritage institutions to develop capacity to make their digital infrastructure resilient to uncertainty whether that is unstable funding or reluctant audiences or both. That capacity needs to be seen as an on-going and long-term investment, developed and maintained internally, spanning, and in service to, the history of an institution rather than any single exhibition or project.

The phrase “designing for patience” is meant to reflect the reality that cultural heritage institutions no longer enjoy a monopoly on the general public’s attention. This shift away from the academy towards large commercial enterprises as well as the proliferation of smaller niche publishers, all developing and promoting ever more cultural production, has been underway for decades. In recent years, and particularly with introduction of the internet and low-cost mobile computing, the shift has picked up speed often being likened to a “firehose” in both its intensity and, increasingly, the inability to meaningfully make any sense of it.

I believe that the broader mission of the cultural heritage sector, and the humanities generally, dictates that we should not be competing with the immediacy of the firehose. Instead we should use digital technologies to develop the infrastructure to ensure that our collections and our holdings are available and accessible and relevant long after the firehose has passed. To be confident enough to believe that people will revisit an idea, to be patient enough wait for them and to be sustainable enough to make both a reality. I do not believe it is possible to do these things without developing the practice and the capacity to do them internally.

In order to discuss these ideas further we first need to spend some time defining what is meant by the terms “digital” and “infrastructure.” The terms “digital,” “digital media,” and “digital technologies” are frequently used interchangeably but, just as often, absent any consensus about what they mean or represent. When someone speaks of digital technologies it is not often clear what they mean. The ambiguity of meaning when two or more people discuss digital technology is often the root of misunderstandings or disagreements about broader topics.

In the “What is ‘Digital?'” appendix to this paper I have included a list of potential meanings that are all equally applicable or relevant when discussing “digital media” and “digital technologies.” This is not an exhaustive list of what might be considered as “digital”, and importantly there are equally valid interpretations that contain only a subset of that list.

For the purposes of this paper the meaning of “digital” should be understood to be more expansive than not. When I speak of “digital technologies”, I am referring to all of things listed in the appendix, whether they are realized or unrealized potentialities.

Equally, the phrase “infrastructure” can mean different things to different audiences in the cultural heritage sector . For the purposes of this paper, infrastructure is defined primarily, but not exclusively, as software projects grouped in to one of four generalized categories.

- External-facing systems, with commonly understood conventions and established boundaries. Typically these are built and operated by commercial vendors with a mass audience.

- Internal-facing systems, with broadly understood conventions specific to the cultural heritage sector. Generally these are built and operated by commercial vendors with a focus on the cultural heritage sector.

- Internal-facing systems, specific to a given institution. Increasingly these are built and operated by dedicated staff in an institution but this internal capacity is still mostly limited to institutions of a certain size and operating budget.

- Public-facing systems, specific to a given institution. Historically these have been built and maintained by third-party agencies with a focus in exhibition design and/or digital applications. In recent years the cultural heritage sector has taken responsibility for some of these systems but by and large they remain outsourced.

Detailed examples of each category are included in the “What is ‘Infrastructure?'” appendix to this paper.

Separations of concern

All of these infrastructure systems, or layers, are used in tandem and in concert with one another during the course of normal operations in a cultural heritage institution. All are “digital” but that does not mean they are the same. Each has unique tolerances and affordances and distinct requirements and skill sets to operate and maintain. Understanding these separations of concern is critical for the cultural heritage sector, particularly when it comes to staffing, because each incurs demands that are not necessarily portable from one category to another.

It is important to distinguish these layers in order to answer one simple question: What is the function of digital technology inside of a cultural heritage institution?

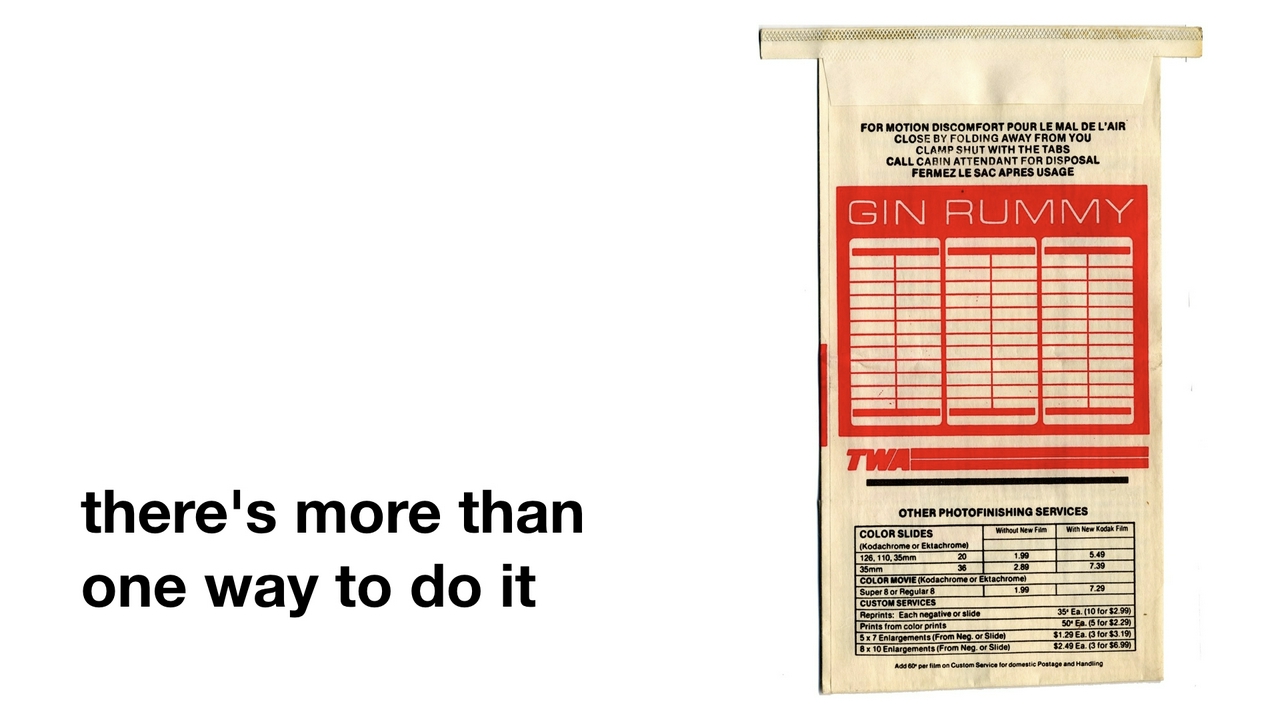

There is not a single “right answer” to this question. But because there are a multiplicity of answers it is important for an institution to be able to articulate their position on the question. To be able to explain why digital technologies are even part of an institution’s mission, independent of which technologies are chosen or how they are deployed. Ideally, the “why” should influence the decisions about the “what” and the “how.” Regardless, the reasons why an institution chooses to entertain digital technologies in the first place will dictate whether the “what” and the “how” succeed or fail.

There is nothing about the dynamics of a “why-what-how” relationship that is unique to digital technologies. It exists in most, if not all, institutional endeavors. Digital technologies, however, have an uncommon ability to force the tensions in the “why-what-how” dynamic to the surface because the promise of “what” they can achieve is so alluring while the realities of “how” to accomplish those things can be unexpectedly complex.

I take the position that the role of digital technologies should not limited to a supporting role, solely as a compliment to an institution’s existing practice and mirroring it in digital media. I believe that the reason “why” a cultural heritage institution should embrace digital technologies, as defined by the list above, is three-fold:

- They provide the tangible ability to produce a multiplicity of avenues, where they did not exist before, into an institution’s collection and the history of its curatorial practice.

- They allow those same avenues to extend beyond the physical footprint of an institution, to reach a global audience and to do so asynchronously. They allow these avenues to stay open, or “always on,” such that people can find them at a time and a place of their own choosing.

- They afford the freedom, both intellectually and importantly financially, to limit the costs, risks and consequences involved in these efforts.

Digital technologies as a whole are a vast canvas so this list is only one possible framing of their qualities and properties. I have chosen these three because they are the qualities and properties that are genuinely novel. These are things that we have not able to do in the past.

Units of currency

The act of revisiting is a touchstone of the humanities. The repeat consideration, and often reconsideration, of a body of work is what distinguishes the humanities from other endeavors. Without this there is little to separate our practice from the cataloging of instruction manuals or traffic reports (both of which are collected by some institutions).

In many institutions the “unit of currency” used to define their efforts remains the exhibition, rather than the collection or its broader mission seen in an historical context. The past, when it is made manifest, is only available in the form of a printed exhibition catalog. An always-on and connected network means that an institution is no longer quantified by the atomic isolation of a building, a single exhibition or an exhibition catalog but rather its ambient presence and the ease with which its present can be connected to its past, not to mention everything else.

In other words, everything a museum does is connected to everything a museum has done not just for those with institutional knowledge but for the greater public audience that an institution exists to serve.

Historically, institutions have undertaken linear and sequential series of themed exhibitions, often both labor intensive and expensive to produce, culminating in big splashy “reveals” designed to buoy an institution for the time it takes to complete the next set of exhibitions. This model of working, sometimes described as “fire and forget,” no longer matches people’s expectations. This is one place where digital technologies can be crafted as a kind of scaffolding that serves to promote the practice of revisiting and to buttress a culture of reflection, alongside existing practice.

The challenge of changing expectations is exacerbated further by a series of issues, unrelated to digital technologies, affecting the cultural heritage sector as a whole:

- The language of the humanities and the cultural heritage sector is often too far-removed from people’s day-to-day lives. The humanities has evolved and promoted a language of discourse that many people simply do not understand or have any means of relating to.

- The cost of participating with or visiting cultural heritage institutions more than once, if at all, is often prohibitively expensive, seen as exclusionary, or simply not worth it because it does not connect with people’s lived experience.

- The assumption on the part of many institutions that a substantial portion, if not the majority, of their visitors will be tourists and likely to only ever visit once. As a consequence little is done to encourage repeat visitation, either in the physical space or online.

At the same time, we are living through a moment in history when the over-arching cultural zeitgeist is a sense of helplessness and a powerful belief that nothing short of radical transformational change will accomplish anything or, worse still, even be noticed. To be a cultural heritage institution in the twenty-first century, then, is to operate in a noisy and cluttered space referred to as the “attention economy” where the very air itself often feels as though it has been weaponized.

Research has shown that museum visitors’ encounters with art are generally brief—an average viewing time of 28.6 seconds per work, according to a 2017 study by Jeffrey and Lisa Smith and Pablo Tinio at the Art Institute of Chicago. That time includes reading the label and, for “a large percentage of visitors” taking selfies, they noted.

(https://www.museus.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/The-Art-Newspaper-Ranking-2018.pdf)

Compounding this reality is a growing belief that there is only a single chance for cultural heritage institutions to capture people’s attention and a disbelief that any of our efforts can buoy themselves longer than an initial first impression. That in order to survive and prosper we must produce ever more elaborate spectacles whose primary function is to serve as attractors giving us equal, or at least improved, footing in an increasingly crowded “attention economy.”

In this context the function of digital is best described as an aspirational signifier. Its manifestation and its reasons for existing are measured only by whether or not it successfully captures people’s attention in an ocean of distractions. In this context anything that does not produce an immediate reaction, or that yields any reluctance on the part of its target audience, is understood as a failure.

As the perceived need for spectacle drives ever more elaborate and costly productions so too do the stakes increase. The impact of a failed production can have significant consequences for an organization’s budget and its appetite for, and importantly its belief in, future efforts let alone revisiting and improving past work.

Even when they do succeed institutions are typically left with a digital infrastructure consisting of expensive one-offs produced by outside vendors that do not age well, almost never interoperate with one another and are ill-suited to adaptation. There is never a past to work from, only a high-priced future to rebuild from scratch.

We also have to look at our own interests and participation in this system as what I call the donee class. Donors give and trustees serve because artists and museum staff beg them to do so. This has become the primary job of directors of institutions in the US. The rising costs of museums, which necessitate huge gifts from wealthy donors, are not primarily driven by board members. They are driven by the ambitious expansion plans of directors, the grand visions of starchitects and the skyrocketing prices of artists’ work. This growth is driven by competition and ambition, not by need. It creates an extremely steep pyramid of resource distribution, in which a few individuals and institutions at the top absorb the vast majority of the total resources in the field. The corporate populist museum needs spectacle and the whole system flatters donors into funding it. (Millar Fisher & Fraser, 2020)

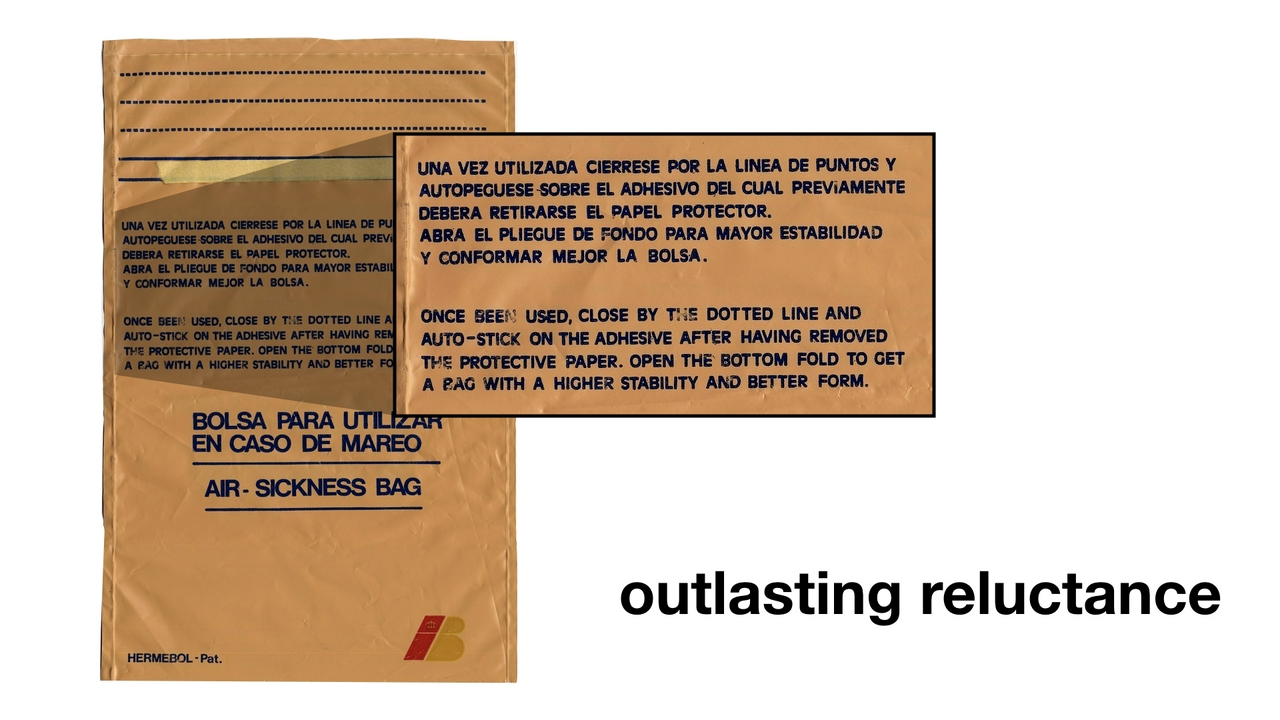

Outlasting reluctance

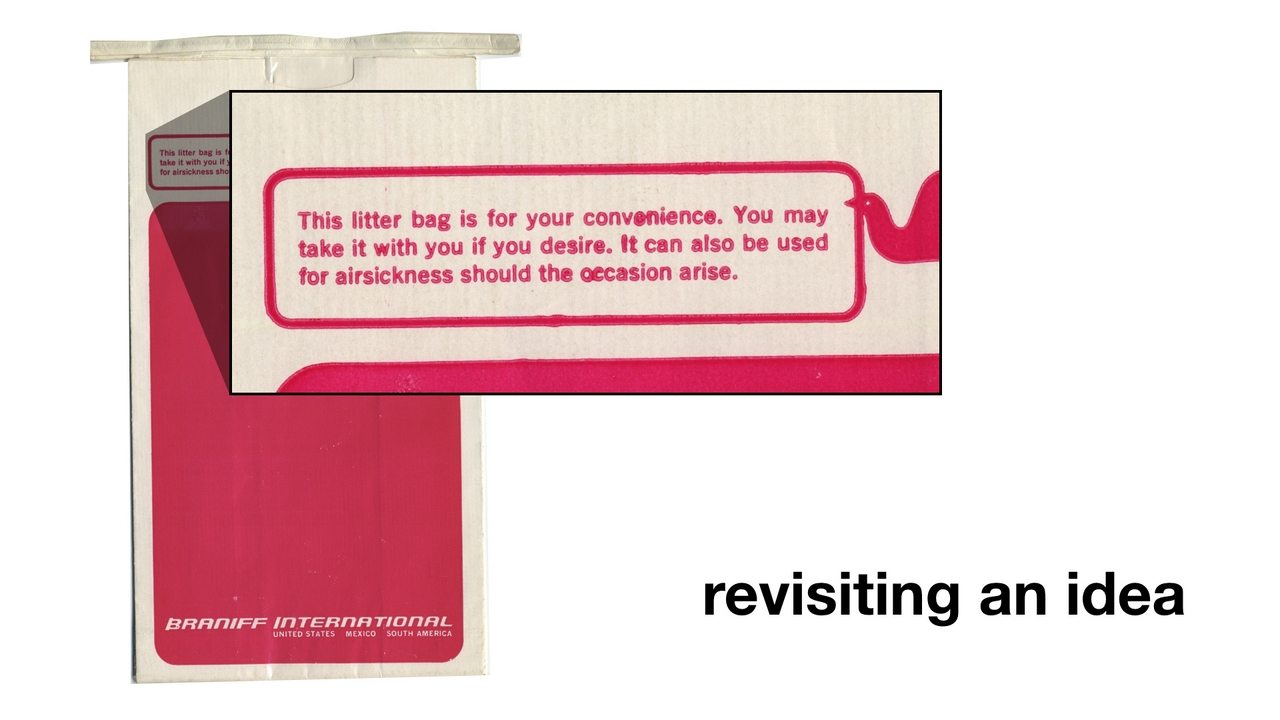

Reluctance, though, is a kind of resistance. It can be understood a necessary survival mechanism. It is a not uncommon reaction to new ideas, new modes of operating or simply new opportunities. It is normal and, in moderation, healthy. The pragmatic act of suspending belief (or disbelief) is sometimes necessary for the simple reason that people are busy and need to prioritize their attention.

But just because someone does not warm up to an idea immediately or on someone else’s schedule does not mean they cannot or will not. Not all connections, or relevancies, are made in the moment. Nor can they be. As often as not those connections are only made after, sometimes long after, a first impression. Just as often if a remembered impression has no way to reestablish that connection it is lost forever.

Without the means to reestablish those connections, without recall, how can there be a revisiting? Without revisiting is there even a cultural heritage to preserve and promote? I argue that being the means of not simply establishing connections, but reestablishing them, is the the principal function of the cultural heritage sector, by whatever means the present makes available.

To that end the role and function of digital technologies inside a cultural heritage sector should be to promote and foster those means. To that end we need to develop and architect those technologies not with the principal aim of a short-term attention economy but instead with the goal of weathering the long-term and usually meandering process of creating meaning across as many audiences as the technologies allow to reach.

With legitimate reason, some people may ask: Is this not the role that for-profit services like the Google search engine or not-for-profit organizations like the Wikimedia Foundation or the Internet Archive perform? Google would certainly like to assume the role of a memory institution in people’s lives as would many members of the Wikimedia community. In many respects they already have. Digital technologies have allowed us to see recall as something we can, that we should be able to, take for granted. Recall has joined the list of things that are only noticed in their absence.

Many, if not most, people already use services like Google or Wikimedia as the primary means of discovery and importantly rediscovery for works in our collections. Are we, as a sector, ready to cede both the control and the responsibility of being the means of discovery for our collections? Are we willing to delegate the decision making process around those means to a third-party, whether or not they operate as a profit-driven enterprise? If not then we need to see these services, and the ways that people are already using them, as a guidepost for the kinds of functionality we need to build and maintain ourselves going forward.

In 2019, I wrote (Cope, 2019) that :

The present offers us the ability to harness the databases, the publishing tools, the programming languages and networks of communities and broadcast channels that have been created, in many instances for entirely other purposes, in the service of our collections and the mandates that our institutions claim. The goals are not new but what is new is that many of those goals are actually within reach now. That these goals are within reach does not, however, mean they are self-realizing.

If an institution believes the role and function of digital technologies is to meet the expectations of the present and to avail itself of the possibilities, near and future, that these technologies suggest, it also needs to recognize that these things are not “self-realizing.”

Concretely, the sector needs to invest, and in some cases re-invest, in dedicated staffing for digital technologies inside cultural heritage institutions. That means investing operational, rather than capital, funds in long-term dedicated staffing for the institution-specific internal-facing and public-facing systems, described in the infrastructure list above. Of these two, the most immediate and pressing need is to develop in-house capacity around internal-facing systems and public-facing online systems and to ensure that capacity both spans and outlasts any one project or single employee.

These are the systems that bridge the collections management systems and any public-facing endeavor an institution undertakes, usually with outside vendors. These are the systems that need to enforce structures and methodologies defined by and tailored to the long-term vision of the institution rather than the short-term needs of an outside vendor. These are the systems that influence everything the public sees and so it stands to reason an institution should have a stake, an opinion and a hand in how they are built.

In doing so an institution itself begins to act as the bridge connecting the many polyglot projects undertaken over time, both internal and external, which would otherwise be short-lived eventually perishing in isolation. In doing so an institution begins to develop the skills, the understanding and crucially the infrastructure to develop and operate its own public-facing systems. To do so not at the expense of third-party vendors but in a way that ensures a more level, and more cost-effective, playing field of possibilities.

In doing so an institution learns to understand and conceive of its digital infrastructure as something that outlasts any one project and fosters confidence in its capacity to produce and sustain long-term and open-ended projects. Comfort with the long-term and with projects that have no fixed end-date is a prerequisite for patience. Patience, in turn, is a prerequisite for developing systems that are able to meet the irregular and meandering needs of the humanities as a whole.

The whole point of a digital team inside an institution is to do those things. Not only the big reveal but “version two” and then “version three” and so on. The purpose of a digital team inside an institution is to build and nurture the infrastructure so that each subsequent project is easier than the last or at the very least creates new challenges rather than retreading the same ground over and over again. These are precisely the sorts of things that outside agencies are not set up to do. It is not their business and no amount of wishful, or magical, thinking on the part of their clients (the cultural heritage sector) will make it so.

“Infrastructure” here should be understood to mean both the technological and cultural scaffolding that supports an institution. Another crucially important function of an in-house team is to be able to respond and adapt to mistaken assumptions along the way. To reduce “the cost of failure”, real or imagined, from being seen as catastrophic to being understood as addressable. (Cope, 2019)

Put bluntly, none of the opportunities and potentialities offered by digital technologies described in this paper are possible without dedicated staff. The opportunities are not “self-realizing.”

There has always been, and remains, a role for outside vendors and for outsourcing parts of an institution’s infrastructure. The mistake that is too often made, though, is to assume those vendors are the correct solution for all of that infrastructure equally. If an institution wants to explore and leverage digital technologies as a core component of their mission then dedicated staffing is the only means by which these goals can be met and, crucially, be made sustainable and affordable. Given a desire to make digital technologies integral to an institution then absent dedicated staff there seems little point in discussing what is or is not possible outside the offerings in a vendor’s promotional material.

To make possible what was previously impossible

The question of staffing and retention in the cultural heritage sector is long-standing and complex, bordering on existential. It quickly points to larger structural problems about how museums are funded and how that funding gets allocated. It highlights the equally complicated problems about how the non-profit sector competes with the salaries and compensation offered by the private sector.

This is especially true when the question is staffing for digital technologies but, in 2020, digital staff is only expensive relative to other functions at a museum. When you look at the kinds of salaries the private sector will bear for that same digital staff it only serves to highlight the unfair salaries the cultural heritage sector promotes in the first place. These salaries help fuel the on-going problem of retention in the sector which makes building and sustaining long-term team-based efforts, digital or otherwise, even harder than they are to begin with. When you consider the sum totals of money that are spent on outside contractors and especially outside technology contractors in the cultural heritage sector it remains something of a mystery how it is that we cannot both raise salaries across the board and sustain in-house digital teams.

To make these ideas concrete consider the following list, all blog posts, or papers, taken from the Cooper Hewitt’s Digital and Emerging Media “Labs” website (https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/) :

- Making “Dive into Color” (Vane, 2018)

- Process Lab: Citizen Designer Digital Interactive, Design Case Study (Adang & Nackman, 2016)

- Traveling our technology to the U.K. (Walter, 2016)

- Museums and the Web Conference Recap: Administrative Tools at Cooper Hewitt and Winning (and losing) hearts and minds of museum staff: Administrative interfaces at Cooper Hewitt (Adang & Brenner, 2016)

- On Exhibitions and Iteration (Brenner, 2016)

- Iterating the “Post-Visit Experience” (Brenner, 2015)

- “Visual Consistency”- tweaking the online collection (Brenner & Ghraowi, 2015)

- Happy Staff = Happy Visitors: Improving Back-of-House Interfaces (Shelley, 2015)

- Redesigning Post-Purchase Touchpoints (Shelley, 2015)

The “digital” team at Cooper Hewitt has never been more than five people at any given point in time. Five people is neither small nor big in a museum context but it is illustrative of what the contemporary technology landscape makes possible. The work above was done in-house and on staff-time, all while maintaining museum operations and the existing digital infrastructure that was launched to support the Pen as part of the museum’s re-opening in 2014. All of this work was built on, extended and informed by the work done for the re-opening. It was done for a fraction of the time and cost that a third-party vendor would have charged to do the same.

I worked at Cooper Hewitt from 2012-2015 and was involved with the museum’s re-opening and the launch of the Pen (O’Kane, 2015). One aspect of that work which has not been addressed as much was the awareness and understanding that in order for the work to be considered a success it had survive the departure of the original team. Success meant ensuring a degree of continuity in staffing that would allow the larger project to survive being “handed off” from one team to the next, or the loss of any one team member.

Ultimately, the value of building and nurturing and sustaining core capacity in-house can be understood as: Making possible what was impossible, or so impractical as to seem impossible, before. In-house teams do not necessarily make that work easy, but they should make it possible.

This is the work

As a sector we have spent a couple of decades making excuses for why “digital” cannot be made core to staffing requirements and the results have ranged from unsatisfying to dismal.

The shift to a “post-digital” museum where “digital [is] being naturalized within museums’ visions and articulations of themselves” (Parry, 2013) will require a significant realignment of priorities and an investment in people. The museum sector is not alone in this – private media organizations and tech companies face exactly the same challenge. Despite “digital people” and engineers being in high demand, they should not be considered an “overpriced indulgence” but rather than as an integral part of the already multidisciplinary teams required to run a museum, or any other cultural institution.

The flow of digital talent from private companies to new types of public service organizations such as the Government Digital Service (UK), 18F (inside GSA) and US Digital Service, proves that there are ways, beyond salaries, to attract and retain the specialist staff required to build the types of products and services required to transform museums. In fact, we argue that museums (and other cultural institutions) offer significant intrinsic benefits and social capital that are natural talent attractors that other types of non-profits and public sector agencies lack. The barriers to changing the museum workforce in this way are not primarily financial but internal, structural and kept in place by a strong institutional inertia. (Chan & Cope, 2015)

In 2020 the question of how to fund, staff and sustain digital teams inside the cultural heritage sector remains largely unanswered. It is made more complicated by similar work undertaken during the previous decade. Have past teams dedicated to technology and “the digital” inside of museums over the last decade, having been given a wide berth and substantial budgets, lived up to their promise? I think it is pretty clear that when you average out all the efforts of the last ten years, including the successes, the answer is no. That is not something most people want to hear but it is important to be clear-eyed and honest when we reflect on past work in order to see where all the good intentions failed in the face of operational realities.

A lot of money and resources were allocated towards those efforts. Many failed or were simply abandoned, leaving in their wake both suspicion and ill-will on the part of donors or others in their respective institutions. This is reality we occupy in 2020 and acknowledging and addressing those concerns and grievances can not be optional. Nor should it be. This is our burden and this is the work. That mistakes were made, though, is not reason enough to give up on the project of building in-house digital capacity.

Arguably in a world where the expectation for the kinds of services and capabilities that digital technologies make possible grows every year there is even more urgency to try again. That mistakes were made simply means we might better understand what not do going forward.

There are no quick fixes for building and nurturing that capacity. It will be a multi-year effort first to establish, or re-establish, credibility for the idea, then to argue for changes in the funding models and then to attract staff. Once those staff are in place it will take time for them to understand the needs and history of the institution, its staff and whatever projects preceded them. How and where a digital team sits in the organization chart may need to be reevaluated. Learning how to correctly identify roles and to scale digital teams in order to work effectively and to ensure succession plans will require trial and effort. It will require a diligence and focus on the part of that staff that was not always present in past efforts.

Larger institutions, with commensurate budgets and staff can play an important role by actively hiring and training junior-level staff with the expectation, encouragement even, that they might leave and take on more senior roles at smaller institutions. If the greater goal is one of building self-sufficiency and sustainability across the sector then, at least in short-term, we need to think about the project as larger than any single institution.

Critical to the challenge of staffing and retention will be an institution’s ability to articulate why they are entertaining digital technologies at all. In order for an institution to attract the staff it needs and wants those reasons why need to be the “intrinsic benefits and social capital” by which a person will choose the cultural heritage sector over the private sector and for those factors to have a higher motivational value than the salaries offered by the private sector.

I find it useful to think about approaching digital technologies in cultural heritage institutions as being akin to a perennial flower garden: In the beginning things are pretty sparse and nothing is very big. Sometimes empty space are filled in with short-living annuals flowers, bright and colorful in the moment but destined to fade away quickly. Most things are expected to survive the winter but it is understood that others do not. Sometimes plants are moved around and some plants do not flower every year. Although this might sound like a recipe for nothing ever getting done, no one, I think, would accuse a dedicated gardener of lacking design or effort.

I suggest that a successful gardener depends on patience and a tolerance for the unknown and even failure in equal measure. The biggest and most beautiful gardens, not unlike cultural heritage institutions, are complex living systems spanning years and even lifetimes. Digital technologies are often mistaken for fully-formed gardens when they are not. They can, however, with care and commitment, be made so and my hope is that this paper has presented a compelling argument for why that work is worth pursuing.

A transformational mass

I would like to close with a thought-experiment, perhaps even a provocation:

Digital technologies inside of cultural heritage institutions have the potential to serve as a kind of transformation mass, offering genuinely unique outlooks and methodologies for approaching and understand not just an institution’s collections and holdings but the institution. This is sometimes labeled as “the digital humanities” but I think that they are closer in spirit and sentiment to an institution’s education department.

Importantly the application of these technologies allows them to make a conceptual leap, similar to the one made by educators, that distinguish them from their curatorial counterpart. That is it, they act as another lens on to the institution and its practice, not better or worse, but recognizably different and valuable on their own terms.

For me, this is the “why” of pursuing digital technologies in the cultural heritage sector. It acts as the foundations for figuring out, and advocating for, the “how”. After that, the only question left is “what” to do next?

Appendix

What is “digital?”

When someone speaks of digital technologies do they mean:

- A medium of production, and the transition from analog to digital materials? For example, graphic design tools like Adobe Illustrator or Photoshop.

- A broadcast medium reflecting the most widely available consumer technology, in the moment? For example, live or on-demand video-streaming services.

- Advances in storage and retrieval technologies and their increasingly availability and affordability? For example, the Amazon Web Services S3 storage service or the Elasticsearch document store and search engine.

- Advances in media processing and other computational manipulation? For example, remote computing platforms like Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud Platform or Heroku.

- Advances in computer vision, machine learning and algorithmic inference. For example, tools like Intel’s OpenCV, Google’s TensorFlow, nVidia’s image in-filling software.

- Free and open source software. For example, the Linux operating system or the Python programming language.

- Low cost, open source hardware platforms and the abundance of programmable sensors. For example, the Raspberry Pi, Arduino, and Feather computing platforms, motion and temperature sensors or near-field communications technologies like RFID and Bluetooth.

- The internet and more generally the assumption of “always on” network connectivity to external resources?

- All of the above bundled as third-party services, often referred to as “software as a service” or “cloud” providers?

- A global audience and communities of interest? For example, social media services like Facebook or Twitter or self-hosted group forums.

- A distributed and asynchronous framework for document persistence and retrieval? For example, the World Wide Web.

- Distributed messaging services, synchronous and asynchronous, for both humans and machines alike? For example, Twitter, group messaging services and other “push” notification systems.

- All of the above bundled as a participatory “experience?” For example, virtual reality, augmented reality, or multi-player games.

For the purposes of this paper “digital media” and “digital technologies” refer to all of these things whether they are realized or unrealized potentialities. This is not an exhaustive list of what may be understood as “digital” and importantly there are equally valid interpretations that contain only a subset of the list above.

What is “infrastructure?”

Equally, the phrase “infrastructure” can mean different things to different audiences in the cultural heritage sector . For the purposes of this paper infrastructure is defined primarily, but not exclusively, as software projects grouped in to one of four generalized categories:

- External-facing systems, with commonly understood conventions and established boundaries. Typically these are built and operated by commercial vendors with a mass audience.

- Internal-facing systems, with broadly understood conventions specific to the cultural heritage sector. Generally these are built and operated by commercial vendors with a focus on the cultural heritage sector.

- Internal-facing systems, specific to a given institution. Increasingly these are built and operated by dedicated staff in an institution but this internal capacity is still mostly limited to institutions of a certain size and operating budget.

- Public-facing systems, specific to a given institution. Historically these have been built and maintained by third-party agencies with a focus in exhibition design and/or digital applications. In recent years the cultural heritage sector has taken responsibility for some of these systems but by and large they remain outsourced.

Example of external-facing systems include an organization’s email or calendaring service or common document formats, such as text processing or spreadsheets. In all cases services and standards are defined by third-parties or commercial vendors targeting a heterogeneous audience. Typically these services are managed by an institution’s information technology (IT) department or, increasingly, as a remote service.

Examples of internal-facing system used sector-wide are commercial collections management or inventory tracking systems. These are systems that contain a mix of data suitable for public release and sensitive or otherwise restricted data used in the course of operations. As with email or calendaring services these tools are often managed by the IT department or as remote services hosted and maintained off-site.

Examples of institution-specific internal-facing systems might be tools for gathering data for an exhibition (Adang & Brenner, 2016) or manipulating data in alternative interfaces than those provided by commercial collections management system. (Berg-Fulton & Newbury & Snyder, 2015) These tools might be developed and maintained by an in-house digital team but may also be the necessary by-product of public-facing systems produced by external vendors.

Examples of institution-specific and public-facing digital systems are in-gallery interactive displays (Alexander & Barton & Goeser, 2013) or a larger physical-digital envelopes designed to foster visitor participation in an exhibition (Chan & Paterson, 2019). Historically these have been developed by outside vendors and maintained only for the duration of an exhibition. Typically these are time and capital expensive projects designed to attract as many people as possible to an institution or to attract donors and other funding sources for future projects. Public-facing systems also include the primary means of accessing information about an institution or its holding, usually in the form of one or more websites. These may be operated by in-house digital staff, an IT department or a third-party vendor.

References

Adang, L. (2016). “Museums and the Web Conference Recap: Administrative Tools at Cooper Hewitt.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2016/museums-and-the-web-conference-recap-administrative-tools-at-cooper-hewitt/

Adang, L. & Brenner, S. (2016). “Winning (and losing) hearts and minds of museum staff: Administrative interfaces at Cooper Hewitt.” MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016. Published January 15, 2016. Consulted February, 2020.

https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/winning-and-losing-hearts-and-minds-of-museum-staff-administrative-interfaces-at-cooper-hewitt/

Adang, L. & Nackman, R. (2016). “Process Lab:Citizen Designer Digital Interactive, Design Case Study.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2016/process-lab-citizen-designer-digital-interactive-design-case-study/

Alexander, J. & Barton J. & Goeser, C. (2013). “Transforming the Art Museum Experience: Gallery One.” In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published February 5, 2013. Consulted February, 2020.

https://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/transforming-the-art-museum-experience-gallery-one-2/

Berg-Fulton, T. & Newbury, D. & Snyder, T. (2015). “Art Tracks: Visualizing the stories and lifespan of an artwork.” MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published January 15, 2015. Consulted February, 2020.

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/art-tracks-visualizing-the-stories-and-lifespan-of-an-artwork/

Brenner, S. (2015). “On Exhibitions and Iterations.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2016/on-exhibitions-and-iterations/

Brenner, S. (2015). “Iterating the “Post-Visit Experience”.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2015/iterating-the-post-visit-experience/

Brenner, S. & Graowi, A. (2015). “‘Visual Consistency’- tweaking the online collection.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2015/visual-consistency-tweaking-the-online-collection/

Chan, S. & Cope, A. (2015) “Strategies against architecture: interactive media and transformative technology at Cooper Hewitt.” MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015. Published April 6, 2015. Consulted February, 2020.

https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/strategies-against-architecture-interactive-media-and-transformative-technology-at-cooper-hewitt/

Chan, S. & Paterson, L. (2019). “End-to-end Experience Design: Lessons For All from the NFC-Enhanced Lost Map of Wonderland .” MW19: MW 2019. Published January 20, 2019. Consulted February, 2020.

https://mw19.mwconf.org/paper/end-to-end-experience-design-lessons-for-all-from-the-nfc-enhanced-lost-map-of-wonderland%e2%80%8a-2/

Cope, A. (2019). “The logical conclusion of the services economy is a museum.” Consulted February, 2020. https://www.aaronland.info/weblog/2019/11/25/toaster/#museums

Jain, A. (2020) “Calling for a More-Than-Human Politics.” Consulted February, 2020. https://medium.com/@anabjain/calling-for-a-more-than-human-politics-f558b57983e6

Millar Fisher, M. & Fraser, A. (2020) “Why Are Museums So Plutocratic, and What Can We Do About It?” Consulted February, 2020. https://frieze.com/article/why-are-museums-so-plutocratic-and-what-can-we-do-about-it

O’Kane, S. (2015). “The Smithsonian’s Design Museum Just Got Some High-Tech Upgrades.” Consulted February, 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2015/3/11/8182051/smithsonian-cooper-hewitt-design-museum-reopening-pen-4k

Shelley, K. (2015). “Happy Staff = Happy Visitors: Improving Back-of-House Interfaces.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2015/happy-staff-happy-visitors-improving-the-interfaces-of-back-of-house-pen-ticketing-tools/

Shelley, K. (2015). “Redisigning Post-Purchase Touchpoints.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2015/redesigning-post-purchase-touchpoints/

Vane, O. (2018). “Making ‘Dive Into Color’.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2018/making-dive-into-color/

Walter, M. (2016). “Traveling our technology to the U.K.” Consulted February, 2020. https://labs.cooperhewitt.org/2016/museums-and-the-web-conference-recap-administrative-tools-at-cooper-hewitt/

This blog post is full of links.

#capacity